The System Is Fragile

Promises Breed Instability

We know that the survival of every economic entity depends on that entity having sufficient cash flows to meet its cash commitments.1 Also true is that any missed payment will cause an expected cash flow to go unrealized.

One person's cash inflow is another person's cash outflow.

(Mehrling 2011, 12)

The liquidity of one entity—its ability to meet cash commitments—depends on the liquidity of anyone who is promising to pay that entity. The more cash commitments there are in the system as a whole, the more entangled everybody's liquidity positions become.

It is in the daily operation of the money market that the coherence of the credit system, that vast web of promises to pay, is tested and resolved as cash flows meet cash commitments.

(Mehrling 2011, 3)

When the money market has trouble covering liquidity gaps2, the system as a whole is under stress. Money-market interest rates spike as everyone bids for the cash they need to satisfy their survival constraints.

As the web of interlocking payment obligations grows more tangled, the system grows more fragile. One missed payment can trigger another. If the metaphorical dominos get too close together, a cascading credit collapse becomes inevitable.

Clip Length: 3:43 (2017 Lec 1, 29:28–33:11)

This is difficult for well-trained economists to appreciate—the inherent instability of credit—because it suggests that the instability is coming from inside the system—from some feature of the system dynamics of the system. And we're used to thinking about equilibrium—thinking about a system in which prices are clearing markets. Supply equals demand. … Instability, if there is any, comes from outside. It comes from political interference with markets. Or it comes from a bad realization of a crop. Or power—you know some some riot somewhere. … Markets are a stabilizing force, and so we always prefer markets over politics. And what this is suggesting is that markets have their own inherent instability.

(2017 Lec 1, 31:28)

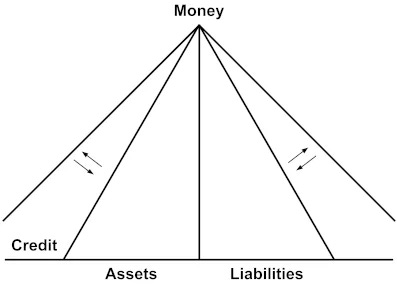

In the above clip, Mehrling highlights the expansion and contraction of credit at various timescales.3 The following diagram, adapted from Mehrling's slides, illustrates the entire hierarchy of money and credit4 expanding and contracting.

Not all credit expansion and contraction is unstable, however. Cycles of flux and reflux are normal and routine (Mehrling 2023). Banks release money (flux) when they lend. They reabsorb that money (reflux) when repaid. A financial crisis is a widespread failure to meet cash commitments and a widespread failure of reflux.

Hyman Minsky famously wrote that "stability is destabilizing" (1982, 26). As long as cash commitments are easy to meet, people will continue entering into new cash commitments. The web will grow more tangled. The dominos will get closer together. This continues right up to the point of financial crisis.

Maybe Minsky is wrong, and there's a way to keep the dominos a safe distance apart. But even if he's right, the money view can help us make the most of our unstable financial system.

References

Hawtrey, Ralph G. 1932. The Art of Central Banking. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Howlett, Alex. 2025a. "Balancing Act: Lining Up Cash Flows in Time." The Survival Constraint (blog). February 10. https://www.survivalconstraint.com/p/balancing-act.

Howlett, Alex. 2025b. "Gap Liquidity: Money, Funding, and Markets." The Survival Constraint (blog). February 13. https://www.survivalconstraint.com/p/gap-liquidity.

Howlett, Alex. 2025c. "Banking Implies Hierarchy: A Natural Money Structure." The Survival Constraint (blog). March 18. https://www.survivalconstraint.com/p/banking-implies-hierarchy.

Mehrling, Perry. 2011. The New Lombard Street: How the Fed Became the Dealer of Last Resort. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mehrling, Perry. 2017. "Lecture 1: Why Is Money Difficult?" Warsaw School of Economics, recorded October 11, 2017. Video of lecture, 1:33:46. https://youtu.be/9DozcacGdYI.

Mehrling, Perry. 2023. "Payment vs. Funding: The Law of Reflux for Today." In Monetary Economics, Banking and Policy: Expanding Economic Thought to Meet Contemporary Challenges, edited by Penelope Hawkins and Ioana Negru, 103–118. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003142317-8.

Minsky, Hyman P. 1982. "The Financial Instability Hypothesis: Capitalist Processes and the Behavior of the Economy." In Financial Crises: Theory, History, and Policy, edited by Charles P. Kindleberger and Jean-Pierre Laffargue, 13–39. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mehrling cites Hawtrey (1932), but Hawtrey's "inherent instability of credit" is not about the survival constraint or a fragile web of promises to pay. Instead, Hawtrey describes how, if left unchecked, runaway expansion or contraction of economic activity will lead to runaway inflation or deflation (Hawtrey 1932, 168). Hawtrey's financial crises are incidental, sometimes occuring at the transition from expansion to contraction.