Gap Liquidity

Money, Funding, and Markets

In the money view, the economy is a network of time-dated cash commitments — promises to pay. Each cash commitment is the liability of whoever made the promise and an asset to whoever expects to receive the payment.

On any given day, if your cash inflows are sufficient to cover your cash outflows, we might say your balance sheet is liquid. If your inflows fall short of your promised outflows, there are three possible types of liquidity you can tap to close your balance sheet's payments gap (Brunnermeier and Pederson 2009; Mehrling 2024, 14:36–18:06).

Monetary liquidity — the ability to spend money in your possession.

Funding liquidity — the ability to borrow money.

Market liquidity — the ability to sell assets for money.

Clip Length: 2:58 (2017 Lec 3, 13:18–16:16)

These three forms of liquidity and the interrelation between them are going to be part of the story. In fact, I'll come to the end to an argument that one of the most important things to understand about the evolution of the monetary system since World War II is that we've moved from a system which was largely focused on monetary liquidity so that people met their payments by using their money balances, and we developed all monetary theory around the idea that that's the only way to do it, and then the system changed, and people started meeting their liquidity needs with funding liquidity, and then people started meeting their needs with market liquidity. And now all three of them are available, but the theory hasn't caught up to this fact about the world.

(2017 Lec 3, 14:05)

Any combination of these three liquidity types may be available to you at any given time, but only monetary liquidity is completely safe. You can always spend your cash.

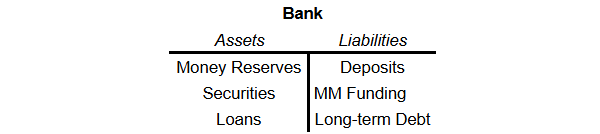

Consider the following balance sheet.

To address a payments gap, the bank has a few options. It could:

dishoard (spend) some of its money reserves (Monetary Liquidity),

borrow in the wholesale money market (Funding Liquidity), or

liquidate (sell) some of its securities (Market Liquidity).

Not all assets are easy to sell. A security, such as a bond, can often be sold on the market, in contrast to loans, which tend to stick around until repaid.

A bank in payments deficit today could be in surplus tomorrow. The money market is where banks and other big firms borrow large amounts of money from each other for short periods of time.

Funding liquidity and market liquidity depend on the general state of the market. To sell an asset or borrow money, you need someone else—a counterparty—to buy your asset or lend you the money. Furthermore, interest rates and prices can move around. And if the market dries up, the counterparties disappear.

Dishoarding is the simplest source of funds. It requires no counterparty. The bank takes money from its pile and uses it to make the payment.

Ultimately, money reserves, borrowing, and selling assets are all ways to relax the survival constraint. Even if you fail to line up your cash flows and cash commitments perfectly, you can tap these forms of liquidity as a source of funds, and you can live to see another day.

References

Brunnermeier, Markus K., and Lasse Heje Pedersen. 2009. "Market Liquidity and Funding Liquidity." The Review of Financial Studies 22 (6): 2201–2238. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn098.

Mehrling, Perry. 2017. "Lecture 3: Fundamentals of the Money View." Warsaw School of Economics, recorded October 13, 2017. Video of lecture, 1:27:49. https://youtu.be/XzMXkJDksrE

Mehrling, Perry. 2024. "Emergency Liquidity Management — Bagehot versus Kindleberger," recorded February 6, 2024. Video, 1:22:44. https://youtu.be/l-Bz53nSAU4