Transactions

It Takes Two

Payments usually pay for something. They serve as one leg of a transaction. The theory of money and banking requires that we think in terms of transactions. Our four payment types from last time1 are transaction building blocks.

The most straightforward transaction is one where someone buys a good or service in exchange for money.

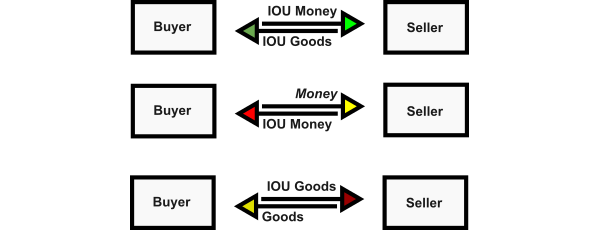

These balance sheets show a buyer exchanging money for goods from a seller.2 There is an assignment of money from the buyer to the seller paired with an assignment of goods in the opposite direction. The buyer and seller swap assets. To help differentiate the two legs of the transaction, I have colored them in two different shades of yellow.

Balance sheets can show us each counterparty's asset and liability position. If we only need to see the transaction, we can use payment arrows.

In his A Market Theory of Money (1989), John Hicks encourages us to look beyond the asset swap.

It will no doubt have been taken for granted that in the markets we have been discussing, the typical transaction was an exchange of some article (good or service) for something that was recognized as being money; and it may also have been taken that the money was simply handed over, as one does when one buys a newspaper in a shop. A useful way of introducing the monetary theory, which will be the subject of the chapters which follow, is to begin by calling into question these two assumptions, asking how far they are justified.

(Hicks 1989, 41)

Following Neilson (2021), we can use our four payment types to construct a four-by-four grid classifying possible two-way transaction types.3

A generic financial transaction involves two simultaneous payments. For example, two counterparties might exchange two different forms of money. Each of the two payments will fall into one of the four categories above (assignment, set-off, issuance, novation), so there are sixteen possible ways that two payments between two entities can be completed.

(Neilson 2021)

Given that we can flip who's on which side of a two-way transaction, there are really only ten two-way transaction types. We will cover each of them in turn as they arise in the Money and Banking lectures (Mehrling 2012).

As an example, let's follow Hicks. What Hicks (1989, 42) calls "the representative transaction of sale or purchase" combines three two-way transactions: a mutual obligation and two asset disintermediations.

The first is the contract between the parties, consisting of a promise to deliver and a promise to pay … ; the second and third consist of actual delivery, one way and the other.

(Hicks 1989, 42)

We call the payment and delivery4 "asset disintermediation" because the two parties each end up holding their respective asset directly rather than a promise for the asset.

Don't worry if you don't understand all the transaction types yet. We're building vocabulary that will help us make sense of things later.

References

Hicks, John. 1989. A Market Theory of Money. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Howlett, Alex. 2025. "Four Ways to Pay: Representing Payment Types." The Survival Constraint (blog). February 23. https://survivalconstraint.substack.com/p/four-ways-to-pay.

Mehrling, Perry. 2012. Economics of Money and Banking. Online course. Coursera. Accessed 2015–2025. https://www.coursera.org/learn/money-banking

Neilson, Daniel H. 2021. "Balance-sheet reasoning: Accounting for Soon Parted." Soon Parted (blog). October 19. https://www.soonparted.co/p/balance-sheets.

(Howlett 2025)

Notice that we've generalized payments beyond money. Here, the seller is "paying" goods to the buyer.

Deviating from Neilson, I have renamed his Secured Loan and Repayment to Mutual Obligation and Mutual Release, respectively.

In this context, "payment" refers to the payment of money, while "delivery" refers to the payment of goods. This won't be the last time we see the same word used to mean slightly different things.

These are great Alex, thanks