Public-Private Monetary Hybridity

Money as a Creature of the Market

Governments and private entities alike use money to make payments and set prices. But who controls the rules of the monetary system? Is it the private sector or the government? Which government? Money is global, after all. It transcends borders.

An issue that runs through the history of money is its intrinsic nature. Is money what the state says is money—legal tender in some formulations that must be accepted in payment of debts, if offered—or is it what people use as money?

(Kindleberger 1993, 38)

In the following clip, Mehrling describes "essential hybridity" (2017a, 7) as the second big hurdle to understanding money. I have recreated his balance sheets further down.

Clip Length: 5:05 (2017 Lec 1, 20:32–25:37)

The system is hybrid. It's public and private. Each one adds something, and they mutually support each other. It's a symbiotic system.

(2017 Lec 1, 24:06)

Like any bank, a central bank monetizes debt by issuing money liabilities.1

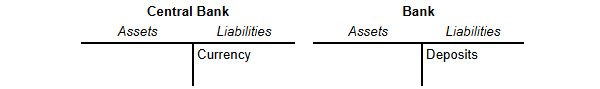

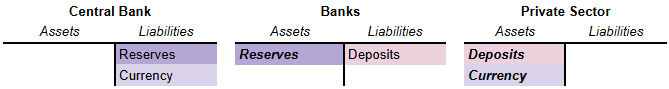

We can take currency (notes and coins) to a bank and get a deposit claim, or vice versa. Both currency and bank deposits are money. The central bank, a public entity, issues one form of money while private banks issue the other.

For banks, their reserve of money takes the form of deposit claims on the central bank.2

See the balance sheets.

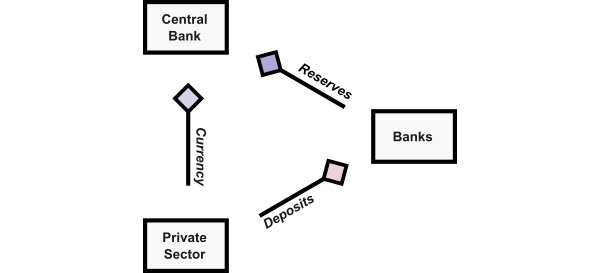

Here it is as a network of money claims.3

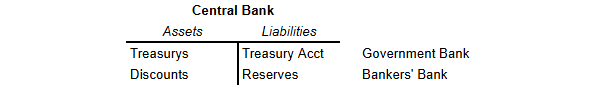

A central bank monetizes both government and private debt. The Treasury—the arm of the government responsible for taxing, spending, and borrowing—keeps a deposit account at the central bank just like the private banks do.

[C]entral banks are part private bankers’ bank and part public government bank, with the proportions shifting over time with financial development and with the exigencies of the state (such as war).

(Mehrling 2017a, 7)

The following balance sheet labels Treasury-issued government IOUs as "Treasurys" and uses "Discounts" to refer to private-sector IOUs purchased at a discount.

The two rows show a government bank and a bankers' bank. However, specific liabilities need not pair with specific assets. Everything is entangled. The central bank is not a government bank coexisting with a bankers' bank. Instead, it is a hybrid of the two.

[B]ecause of the risks to which any bank is in principle subject, a banking system as such has a tendency to develop a centre, being a bank, or group of banks, on which other banks come to rely. This can come about without any action by government. The relation so established can indeed transcend the boundaries of nations.

(Hicks 1989, 98)

Central banks emerge to help the monetary system better manage the survival constraint. In doing so, they serve the public interest, as well as the interest of individual participants in the monetary system, including governments.

Centralization is natural. Money and banking connect everything. Labeling the economy as distinct public and private sectors doesn't change that. Beneath the labels, the monetary system is all one thing.

References

Hicks, John. 1989. A Market Theory of Money. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Howlett, Alex. 2025a. "Four Ways to Pay: Representing Payment Types." The Survival Constraint (blog). March 1. https://survivalconstraint.substack.com/p/four-ways-to-pay.

Howlett, Alex. 2025b. "The Alchemy of Banking: Transmuting Promises into Money." The Survival Constraint (blog). March 1. https://survivalconstraint.substack.com/p/the-alchemy-of-banking.

Kindleberger, Charles P. 1993. A Financial History of Western Europe. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mehrling, Perry. 2017. "Lecture 1: Why Is Money Difficult?" Warsaw School of Economics, recorded October 11, 2017. Video of lecture, 1:33:46. https://youtu.be/9DozcacGdYI

Mehrling, Perry. 2017a. "Financialization and Its Discontents." Finance and Society 3 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v3i1.1935.

(Howlett 2025b)

Banks can also hold some of their reserves in the form of currency.

This representation is analogous to the payment diagrams we've seen before (Howlett 2025a).