Money as Credit

The Purest Money Is Paper

In the previous post, we established that the liabilities of some entities serve as money for others.1 In the lecture clip, however, Perry Mehrling says something that doesn't quite map onto this conception of monetary hierarchy.

Credit is a promise to pay money, and money is the highest form of credit.

(2017 Lec 1, 28:22)

This sounds a bit circular. Is money a promise to pay money?

Clip Length: 20 Seconds (2017 Lec 1, 28:20–28:40)

Henry Dunning Macleod (1866) provides a definition of credit that can help us unpack Mehrling's statement.

Credit is anything which is of no direct use, but which is taken in exchange for something else, in the belief or confidence that it can be exchanged away again.

(Macleod 1866, 18)

Here, credit does not have to be a promise to pay money—or a promise at all. Credit is anything whose value derives from what it can be exchanged for.

Money, then, is the standard form of credit that we use to settle debts.

Now, as money is always exchangeable throughout the commercial community, it is evident that it has a general and a permanent value; that is, it is exchangeable among all persons and at all times, and in all places of the same country. It is therefore the highest and most general form of credit.

(Macleod 1866, 18–19)

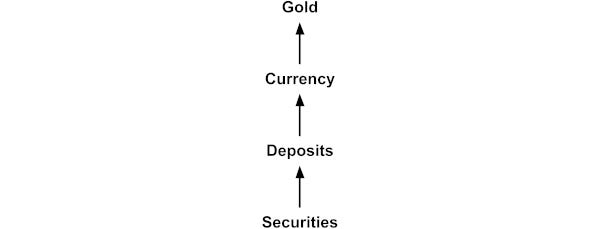

There is no such thing as non-credit money. Even gold, though it has some direct use, is a form of credit when we use it as money. Every layer of Mehrling's hierarchy (2017 Lec 1, 25:45) fits Macleod's definition of credit.

Instruments at different layers can all be fully money as long as they serve as the standard settlement instrument for their respective layer.

Henry Thornton (1802) emphasizes that money, irrespective of its form—whether gold, currency, or deposits—serves as a claim on goods and services.

Money of every kind is an order for goods. … It is merely the instrument by which the purchasable stock of the country is distributed with convenience and advantage among the several members of the community.

(Thornton 1802, 260)

This perspective underscores an intrinsic link between money and the real economy. Money is not a promise to pay money. Money is a claim on goods and services. And other money-denominated credit is a claim on money.

Credit is to money what money is to commodities.

(Daniel Webster, quoted in Macleod 1866, 20)

I find the preceding description of money compelling, but Mehrling might not. He likely intended his circularity.2

The most real thing is money, but money is nothing more than a form of debt, which is to say a commitment to pay money at some time in the future. The whole system is therefore fundamentally circular and self-referential. There is nothing underneath, as it were, holding it up.

(Mehrling 1999, 138)

Money is either a claim on goods or a circular claim on itself. Either way, money, in its ideal platonic form, is a credit claim. Commodity monies such as gold are merely an approximation of that ideal.

References

Howlett, Alex. 2025. "Banking Implies Hierarchy: A Natural Money Structure." The Survival Constraint (blog). March 18. https://www.survivalconstraint.com/p/banking-implies-hierarchy.

Macleod, Henry Dunning. 1866. The Theory and Practice of Banking. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, & Dyer.

Mehrling, Perry. 1999. "The Vision of Hyman P. Minsky." Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 39 (2): 129–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(99)00029-3.

Mehrling, Perry. 2012. Economics of Money and Banking. Online course. Coursera. Accessed 2015–2025. https://www.coursera.org/learn/money-banking

Mehrling, Perry. 2017. "Lecture 1: Why Is Money Difficult?" Warsaw School of Economics, recorded October 11, 2017. Video of lecture, 1:33:46. https://youtu.be/9DozcacGdYI

Thornton, Henry. 1802. An Enquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Paper Credit of Great Britain. London: J. Hatchard and F. and C. Rivington.

Mehrling's Economics of Money and Banking lectures (2012) contain little discussion of the basis for the monetary standard or the interface between money and the real economy. However, the readings that accompany the lectures explore these topics a bit more.

this is such a great post, and I like that you have all the references. This is the most concise and direct explanation I have seen.